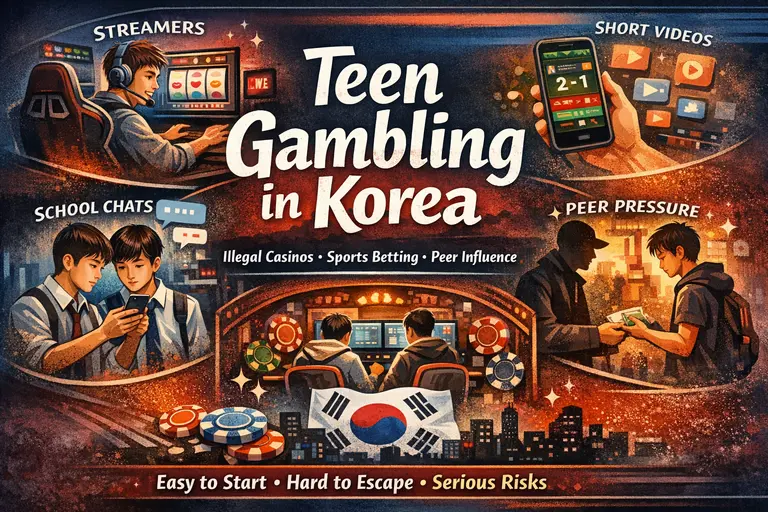

Teen gambling addiction in South Korea: how illegal online casinos pull minors in — and why streamers accelerate the fall

Teen gambling addiction is a dependency sold to minors wrapped as “content,” “a show,” and “adult play.” Today a child watches a clip; tomorrow they “try it out of curiosity”; the day after, they’re already hiding their phone, lying about money, and living in “I have to win it back” mode. This isn’t a story about “weak will.” It’s a story about a mechanism that learns from emotions — and an environment that helps that mechanism spread.

The dirtiest part starts long before adulthood. It almost never looks like “they accidentally ended up on a site.” In reality, the chain increasingly works like this: they show “easy money” → a teen repeats it → one kid pulls in a friend → then it spreads through school chats, friend groups, and meetups. And the stronger the external pressure (blocks, bans, loud news cycles), the more often the problem doesn’t disappear “to zero,” but goes deeper: into closed channels, workarounds, and darker zones.

Official statistics (real numbers): what the school sample already shows

South Korea has an official school-based study for 2024 (scale: 605 schools, 13,368 students — grades 4–6 in elementary school, plus middle and high school). It includes figures that are important to “read correctly.”

- 4.3% of students said they had tried gambling at least once in their lifetime.

- Among those who reported experience, 19.1% said they had also played within the last 6 months.

- 27.3% reported that even without personal participation, they had exposure through their environment: seeing/hearing about gambling via friends, etc.

- In the group that played in the last 6 months, 48.4% mentioned using someone else’s identity/data, and 24.4% reported betting through an intermediary (proxy betting).

- Proxy betting becomes easier with age and looks increasingly “normal”: about 5.6% in younger ages, and roughly 21.5% among middle schoolers.

And here’s the key point. If you look at these numbers superficially, they may not look like a “major catastrophe.” Because official statistics capture what people are willing to admit out loud. Teen gambling, by its nature, is largely pushed into a hidden zone.

Why this is only the tip of the iceberg: it’s not “just 4.3%”

If you focus only on “personal experience,” it’s easy to fall into the trap: “So it’s a minority, right?” But next to it is 27.3% (exposure through peers). That means a social environment already exists inside schools.

- they discuss “where you can play,”

- they know “how to top up,”

- they share “where it’s easier and checks are lighter,”

- and, most importantly, they normalize it with lines like “everyone’s tried it.”

And the fact that official answers already surface workarounds like someone else’s data (48.4%) and proxy betting (24.4%) means: the “age barrier” didn’t stop the market — it simply moved onto workaround rails. This is exactly the zone parents and schools see the worst.

Plus, teens have the perfect protection for hiding the problem: shame, fear of punishment, fear of family reaction, the habit of quickly wiping traces from a phone — and, above all, the belief that “I’m in control.” That’s why the real scale is almost always bigger than what people admit officially.

Why it spreads faster in Korea: the phone + the speed of the environment

In South Korea, teen life is almost entirely inside the phone: communication, entertainment, purchases, instant transfers. Social spread is fast too: links, short videos, “how-to” posts fly around. Even if a child doesn’t gamble, they can end up inside a group where it’s already being discussed and shown.

This creates a “contagion” effect. Illegal gambling info spreads easily — almost like a meme — but the consequences are far heavier.

Why teens “stick” faster: the brain learns from anticipation, not the win

Online casinos and illegal betting are built so the brain learns not from winning, but from anticipation. It’s not only “the payout” — it’s the chemistry of the process: tension, risk, adrenaline, hope. The most toxic hook is the “almost won.” You actually lost, but it feels like “it almost worked,” and the brain pushes you to continue.

In adolescence this mechanism hits harder: impulsivity is higher, self-control isn’t fully formed yet, and peer influence and comparison (“who’s cooler”) are powerful. So the loop closes quickly: one more try → need to win it back → hide it → lie → lose more.

The entry point doesn’t start with a site — it starts with “atmosphere”

Many parents think: “My child won’t go to a casino site.” But the entry point often opens not through a site, but through peers and content.

At first it’s “a small thing,” “like coffee,” “just a test” — words that sound safe. Then instructions start circulating: “where to go,” “how to top up,” “where checks are lighter.” Then comes normalization: “everyone tried,” “it’s no big deal,” “it’s just a game.” Once a child lives through that cycle in their body even once, it’s no longer logic that drives them — it’s habit.

Streamers and influencers: the fastest accelerator of involvement

Today the strongest accelerator isn’t banners and not links in chats. It’s streamers and influencers.

Teens react poorly to “official bans.” But they react to a familiar face they trust. Someone builds a “one of us” image for years: they play, joke, share everyday life, create closeness. And then at some point they show gambling as “content” — under words like “experiment,” “luck test,” “challenge.” In that moment, the ad disappears — the show remains.

Gambling streams hit harder than ads because they don’t look like ads. They look like “real life”: emotions, big numbers, explosions on screen, the illusion of “I could do that too.” A teen is hooked not by legal risk, but by the emotion of the frame.

The most dangerous part is that what’s being sold isn’t money — it’s an image: status, adulthood, “fast success.” Once that picture is planted in the head, the word “illegal” breaks through worse — because emotion got there first.

What teen addiction looks like: warning signs you can’t ignore

A child won’t say: “I have a problem.” They’ll hide it, get angry, deny it. So you have to watch behavior.

- Money disappears: allowance runs out too fast, strange transfers appear, requests to “borrow from friends” or “I urgently need it” increase.

- The phone turns into a safe: hidden tabs, instant screen switching, deleting notifications, painful reactions to questions.

- The “win-it-back language” appears: “one more time,” “I almost got it back,” “just a little left,” “I’ll recover it now.”

- The life rhythm breaks: sleep, school, interests, and the social circle narrow sharply.

- Explosive reactions to limits: touch internet access or payment access — and disproportionate anger and aggression flare up.

What families should do: don’t break the child, but don’t let the problem slide

The most common mistake is trying to “win” with shame and force. Yelling, threats, taking the phone often backfires: the child goes deeper into hiding, becomes more secretive, and learns to bypass bans. But “they’ll grow out of it” doesn’t work either: the “win-it-back” loop doesn’t switch off by itself.

A workable stance is this: we’re not at war with the child — we’re at war with the problem. The tone is calm, but the meaning is firm: “this is already a dangerous signal, and we won’t ignore it.” Then — not moralizing, but mechanics: explain that gambling is built as a system that drains money and hooks you through emotions.

In parallel, you need to cut off the “fuel” — money and access to payments. But if you do it as punishment, you’ll destroy contact and the child will move into an even darker zone. It has to be framed as a “safety fuse,” not a “penalty.” The less humiliation and the longer dialogue remains, the higher the chance you’ll see the real picture. When dialogue breaks, reality disappears into the shadows faster.

If debts are already visible, emotional blow-ups are sharp, there are attempts to borrow or steal money, and constant “I have to win it back” — this is closer not to discipline, but to addiction. You shouldn’t drag time here.

Key takeaway

Teen gambling addiction in South Korea lives in the phone, in school chats, in short videos and streams. Official numbers show only the starting picture. The iceberg shows itself differently: a high share of “peer exposure,” the presence of workarounds (someone else’s data, proxy betting), and easy normalization via “it’s just a game.”

Streamers turn gambling into a show and open the door. Peer circles spread links and “how-to” posts. Money and payment access become the fuel that accelerates addiction.

If adults truly want to protect a child, you can’t believe in “one block.” It matters not to miss early signals, not to break contact, to control money and payment access, and if the “win-it-back” loop has already formed — to bring in help as quickly as possible.

How Korea’s gambling market really works

In Korea, conversations about gambling are always loud. In the news and official statements you constantly hear phrases like “stepped-up raids,” “mass detentions,” “eradicating the illegal market.” From the outside, it looks like regulation is harsh and there’s almost no choice. But if you look not at press releases, but at the city’s reality, you get the feeling the picture doesn’t match one-to-one.

👉 Read more

FAQ

Does this article explain “how to” engage in illegal gambling?

No. The purpose of this article is to explain how teen gambling addiction spreads, what structure keeps a person hooked, and why risks grow. There are no step-by-step instructions here on bypassing restrictions or “how to use” illegal services.

Why is teen gambling growing in Korea? What’s the main reason?

Because the combination of “life through the phone,” the fast spread of habits among peers, and the influence of short videos/streaming makes the “curiosity → first try → win-it-back” loop very easy. And if demand doesn’t disappear due to blocks and bans, it often moves into more hidden channels.

Why are streamers so dangerous?

Because “a show that doesn’t look like an ad” works stronger than banners. When someone people trust shows gambling as content, teens react first to emotion and on-screen atmosphere — not to legal risks — and the illusion “I can do that too” forms easily.

What signs can suggest a child may be developing a gambling problem?

If money disappears too fast or strange transfers increase; the child hides their phone excessively; often says “one more time,” “almost,” “need to win it back”; sleep/school/relationships collapse; and limits on internet or payments trigger explosive aggression — these can be warning signs.

What should parents do first?

Don’t try to “defeat” the child with humiliation and force — it’s important to keep the conversation and acknowledge the problem together. In parallel, manage the fuel of addiction as a “safety fuse”: money and access to payments. And instead of tightening surveillance (which pushes the child deeper into secrecy), it’s more effective to explain “why it’s dangerous” through mechanism and consequences.

What if there are already debts or attempts to steal money?

At this stage, it’s closer to addiction than discipline. The longer you wait, the higher the risk of deterioration. It’s safer not to rely “only on the family,” but to involve professional resources as early as possible: counseling and treatment.

Can the problem be solved with blocks alone (sites/apps/ISP)?

Most often — no. Blocks can make access harder, but if demand remains, workarounds and intermediaries appear quickly. So blocking is only a supporting measure. The key is early detection of warning signs, control of money and payments, keeping dialogue, and — when needed — quick access to professional help.

Why are school chats and “peer culture” so important?

Because teen gambling can’t be explained by “willpower” alone: it grows fast in an environment where information spreads and becomes normalized. If conversations start circulating like “where it works,” “how to top up,” “where it’s easier,” that can be a sign a dangerous ecosystem has already formed.